en

names in breadcrumbs

The following is a late 18th Century English recipe for herring pie, perhaps similar to the one required of the city of Yarmouth in its city charter. The author of this taxon account adds this recipe ONLY as proof that herring have been used in a variety of different foodstuffs for some time throughout history, and NOT as a suggestion for any future meal.

"A HERRING PYE: Scale, gut, and wash them very clean, cut off the heads, fins, and tails; make a good crust, cover your dish, then season your herrings with beaten mace, pepper and salt; put a little butter in the bottom of your dish, then a row of herrings; pare some apples, and cut them in thin slices all over, then peel some onions, and cut them in slices all over thick, lay a little butter on the top, put in a little water, lay on the lid, and bake it well." (Gellory, 1762)

Although little is known of the behavioral reasons behind their noise productions, Clupea pallasii pallasii are known to produce and perceive sounds. Noise is usually produced at night by is probably the result of forceful ejection of air from the anal duct. The frequency of noise production did not change due to feeding. This noise production tends to increase with increasing numbers of herring in a school, leading to speculation that there is a social component to noise production (Wilson, Batty, and Dill, 2003).

Communication Channels: acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Clupea pallasii pallasii is not an endangered species. However, with heavy fishing in the 1960s and a lack of recruitment in the 1970s, Atlantic herring fisheries crashed. Although the fishery recovered since then, its vulnerability, especially with increased potential of climate variability has lead the several countries to conduct studies looking at sustainable herring harvests (Alheit and Hagen, 1997).

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Clupea pallasii pallasii eggs are laid on rocky to sandy substrate, rarely on mud, from 3.7 m to 54.9 m on the North American side of the Atlantic. In Scandinavia, depths of 182.9 m have been recorded. Fertilization may take place in spring, summer, or autumn, according to locality and subtype of Atlantic herring (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

Incubation lasts anywhere from 10 to 40 days, depending on local water temperatures. Colder temperatures (roughly 3.3 deg C) indicate a longer incubtion time. Incubation can take place in water temperatures of up to 15 deg C. Temperature ranges above and below these limits produced no viable hatchings (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

At the time of hatching, Clupea pallasii pallasii are about 6 mm long. Their small yolk sack is usually completely absorbed by the time they reach 10 mm in length. At 15 to 17 mm, the dorsal fin forms. The anal fin forms when Atlantic herring reach about 30 mm. Ventral fins become visible at 30 to 35 mm. The tail becomes well-forked at around this length as well. Only when Atlantic herring reach 40 mm do they start to fully resemble mature herring (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

At roughly 2 years of age, Clupea harenga are about 19 to 20.5 cm in length, and start to accumulate large amounts of fat in the body tissue and viscera during warm months. This fat is lost in the winter and at the approach of sexual maturity (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

Before large-scale fishing operations started in North America, the vastness of the shoals of Atlantic herring "became absolutely a nuisance" in the Chesapeake Bay area (Buffon, 1793). Clupea pallasii pallasii can be very susceptible to pollution and being beached during large storms. Bigelow and Schoreder (1953) describe a "slaughter of herring" that started in October 5, 1920 and resulted in a tidal harbor becoming completely covered with dead herring. The large anoxic zone resulting from the decomposition of the massive number of dead herring caused even more fish kills.

Herring fisheries in both Europe and North America have been important sources of protein in diets going back centuries. Jones (1795) indicates that the Dutch fishery dates back to 1167, and Alheit and Hagen (1997) indicate the presence of a Swedish fishery dating back to the 10th Century. In North America, the Native Americans were the first ones to use a system of weirs to catch herrings, as they were difficult to catch using the traditional methods of hook or spear (Gulf of Maine Aquarium, 2004).

The love of Atlantic herring as a foodstuff in Britain was well captured by Jones (1795): "Yarmouth has long been famous for its herring [fare], which was regulated by an act in the 31st [year] of Edward the Third: and that town is obliged, by its charter, to send to the sheriffs of Norwich 100 herrings, to be made into twenty-four pies, by them to be delivered to the lord of the manor of East Carleton, who is to convey them to the king."

The Atlantic fishery continues to be a popular, if not a highly economic, one. In 2001, the New England herring fishery had an estimated total value of $15,615,237 in U. S. dollars (Parker, 2003). Similar fisheries are found throughout the range of Clupea pallasii pallasii.

The nutritional information for raw Atlantic herring is: 158 Calories/100g, 17.96g protien/100g, 0.0g carbohydrate/100g, 2.04g saturated fatty acid/100g, 3.736g monosaturated fatty acid/100g, 2.133g polyunsaturated fatty acid/100g

Positive Impacts: food ; research and education

Herring are a critical part of the Atlantic ecosystem, being a prey species for a large variety of species. They are pelagic plankton feeders (Gulf of Maine Aquarium, 2004b).

Atlantic herring are also the host of several parasitic species. In a study of 220 Norwegian spring spawning herring, Tolonen and Karlsbakk (2002) detected 11 parasitic species: the coccodians Goussia clupearum and Eimeria sardinae, spores of the myxozoan Ceratomyxa auerbachi, adult trematodes Hemiurus spp., adult and larval nematodes Hysterothylacium aduncum and Anisakis simplex, and Cryptocotyle lingua metacercarial infections.

In the late 1700s, Leeuwenhoek hypothesized that Clupea pallasii pallasii was a plankton feeder, stating that "Seeing these things, I did not wonder that fishermen should imagine Herrings have no food in their stomachs, because Herrings do, in my opinion, feed on such small fishes ["animacules"], that they cannot take in sufficient quantities of them to distend their stomachs, as we see in other fish; and hence it is said, that Herrings have no food in within their stomachs." (Leeuwenhoek, 1798)

With the advent of better microscopes and observational techniques, it was found that plankton (the "animaclues" of Leeuwenhoek's time) that Clupea pallasii pallasii feeds upon, starting with larval snails, diatoms, peridinians when first hatched, moving on to copepods, amphipods, pelagic shrimps, and decapod crustacean larvae when they reach adulthood (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

Animal Foods: fish; eggs; mollusks; aquatic or marine worms; aquatic crustaceans; other marine invertebrates; zooplankton

Plant Foods: phytoplankton

Primary Diet: planktivore

Older references of Atlantic herring indicate that populations may move between different coastal regions after a number of years, disappearing off the coast of Norway, while showing up on the shores of Germany (Buffon, 1793). This process can be explained by climatic forcing of Atlantic herring migration occuring on a decadal cycle (Alheit and Hagen, 1997) as well as fluctuations in spawning caused by switches in recruitment in between northern and southern populations in the North Sea (Corten, 1999).

Clupea pallasii pallasii are closely related to the Pacific herring Clupea pallasii pallasii, which resides mainly in the northern Pacific Ocean. Recent genetic evidence indicates that these two species diverged roughly 1.3 million years ago (Domanico, et al., 1996).

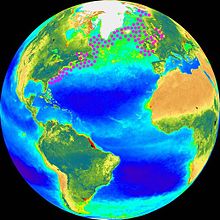

Biogeographic Regions: atlantic ocean (Native )

Other Geographic Terms: holarctic

Atlantic herring Clupea pallasii pallasii are found in the palagic zone of marine waters, as well as coastal zones of throughout their geographic reach.

(Note: the maximum depth value given is based on a value of 50 fathoms (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953)).

Range depth: 36.576 to 0 m.

Habitat Regions: saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; coastal

Other Habitat Features: intertidal or littoral

Clupea pallasii pallasii may live up to 20 years.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 20 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 22.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 19.0 years.

Clupea pallasii pallasii grow to about 17 inches (45.72 cm) and can weigh up to 1.5 pounds (0.68 kg) (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953; Gulf of Maine Aquarium, 2004d). Atlantic herring stocks in the Baltic Sea have recently seen significant decreases in weight-at-age in all age-classes with larger declines in northern populations than southern populations, and in younger age groups than in older groups (Cardinale and Arrhenius, 2000). The result of this decrease in weight-at-age could be indicative of a change in the average size of all Clupea pallasii pallasii populations, or it may only be a case of Baltic Sea populations.

Clupea pallasii pallasii are laterally compressed, with a moderatly pointed nose, a large mouth at the tip of the snout, and a projecting lower jaw. They have a "saw-toothed keel" belly and a deeply forked tail. The keel is only weakly sawtoothed as compared to other members of its family. The dorsal fin is situated roughly midway down the back, and the abdominal fins are located almost directly below it. There is no adipose fin. The scales are large and loosely attached. The key anatomical difference between Clupea pallasii pallasii and other members of the family is an oval patch of small teeth on the vomer bone at the center of the roof of the mouth (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

The body color is of a deep steel blue or greenish blue, with silver sides and belly. Ventral and anal fins are translucent white. The pectorals are dark at their base and along the upper edge. The caudal and dorsal fins are also dark(Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953).

Range mass: 0.68 (high) kg.

Range length: 45.72 (high) cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike

As Atlantic herring are the prey species of many species of fish, mammals, and birds, herring are almost always found in schools (Bigelow and Schoreder, 1953). Some schools display elaborate patterns (Gulf of Maine Aquarium, 2004b). These schools may be quite large, stretching several miles in length and visibly darkening the waters (Jones, 1795).

Clupea pallasii pallasii is a prey species of cod, pollock, haddock, silver hake, striped bass, mackerel, tuna, salmon, dogfish (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953), harbor porpoises Phocoena phocoena, harbor seals Phoca vitulina, gray seals Halichoerus grypus, Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica, razorbills Alca torda, common terns Sterna hirundo, arctic terns Sterna arctica, killer whales, baleen whales (Gulf of Maine Aquarium, 2004b), and humans Homo sapiens.

Known Predators:

Atlantic herring aggregate into massive schools in the late summer and early fall. In the western Atlantic, they move into coastal waters at various locations in the Gulf of Maine and offshore banks of Nova Scotia to spawn. Spawning times vary for different populations of Atlantic herring.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Clupea pallasii pallasii uses external fertilization of eggs. As female herring release eggs, male herring release clouds of milt simultaneously. Herring are fat prior to spawning, after months of eating plankton blooms.

Mature eggs make up a large portion (20%+) of the female's body weight. The fecundity of herring females is typically in the range of 20,000-50,000 eggs per female, although a large female herring can lay as many as 200,000 eggs. Herring are iteroparous and generally live to spawn repeatedly for several years. After spawning, their weight declines with the loss of gametes and associated fat content.

Breeding interval: Atlantic herring usually spawn after reaching 25.5cm.

Breeding season: Atlantic herring may spawn in spring, summer, or autmn, depending on local conditions and the subspecies of herring.

Range number of offspring: 200000 (high) .

Average number of offspring: 20000-50000.

Range gestation period: 10 to 40 days.

Average gestation period: 11 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 3 to 6 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 4 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 3 to 6 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (External ); broadcast (group) spawning; oviparous

There is no evidence that Atlantic herring invest any energies toward parenting after they spawn.

Parental Investment: pre-fertilization (Provisioning)

An harink (Clupea harengus), liester harinked, a zo ur pesk mor.

L'areng (Clupea harengus) és una espècie de peix de la família dels clupeids i de l'ordre dels clupeïformes.[4] L'areng de l'Atlàntic (Clupea harengus) està estretament relacionat amb l'areng del Pacífic (Clupea pallasii), ja que recents estudis genètics indiquen que aquestes dues espècies van començar a divergir fa aproximadament 1,3 milions d'anys.[5]

De forma similar a la sardina els mascles poden assolir 45 cm de llargària total i 0,68 kg de pes. Té el cos comprimit amb la mandíbula inferior prominent, l'opercle llis, les Parpelles adiposes poc marcades. La carena del ventre la té més marcada que la de la sardina. Dors blau fosc, més clar a la part superior dels flancs. El ventre és argentat. Opercle amb tonalitats daurades. Les escates són grosses. No hi ha dimorfisme sexual.[6][7][8]

És comú a l'Atlàntic (des de les costes de Terranova, els Estats Units i Groenlàndia fins a les Illes Britàniques, el Mar del Nord i el Mar Bàltic) i no es troba en aigües ibèriques.[9] Només viu a temperatures inferiors als 12 °C i fins als 360 m de fondària.[10]

Forma grans moles de molts individus per a defensar-se dels atacs dels depredadors,[11] amb migracions complexes tant a la recerca d'aliment com per a fresar. Pot viure fins als 20 anys.[12]

Menja petits copèpodes planctònics, larves de mol·luscs i diatomees en el seu primer any de vida i després es nodreix fonamentalment d'amfípodes, gambetes pelàgiques i larves de crustacis decàpodes quan arriba a l'edat adulta.[13] Troba el seu menjar emprant el sentit de la vista.[14][15]

És sexualment actiu entre els 3 i els 9 anys.[16] Cap al mes de març migra de les profunditats cap a la superfície per reproduir-se i és el moment que s'aprofita per a pescar-lo. Cada població es reprodueix, pel cap baix, una vegada cada any.[14] La femella pon entre 20.000-40.000 ous, els quals quedaran fixats amb mucus als fons de sorra o de grava. La incubació dura entre 10 i 40 dies (depenent de la temperatura de l'aigua)[15] i dels ous naixeran uns alevins transparents i d'uns 5 mm de longitud.[17]

A banda de ser pescats pels humans (Homo sapiens) és depredat per una àmplia gamma d'espècies, com ara el bacallà (Gadus morhua), els túnids, la mòllera, Myoxocephalus octodecemspinosus, Gadus macrocephalus, el merlà, el rap americà (Lophius americanus), el rap blanc (Lophius piscatorius), el lluç platejat (Merluccius bilinearis), el lluç (Merluccius merluccius), Merluccius productus, l'halibut negre (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides), el tallahams (Pomatomus saltatrix), el salmó europeu (Salmo salar), Sebastes maliger, Sebastes nigrocinctus, Sebastes ruberrimus, Centropristis striata, Chelidonichthys gurnardus, el peix espasa (Xiphias gladius), Lycodes frigidus, Hippoglossoides platessoides, l'escorpí de mar d'espines curtes (Myoxocephalus scorpius), l'espinós (Gasterosteus aculeatus), Myxine glutinosa, el bec de serra gros (Mergus merganser), la gavineta de tres dits (Rissa tridactyla), el mascarell (Morus bassanus), la foca grisa (Halichoerus grypus), la foca de Groenlàndia (Phoca groenlandica), la foca comuna (Phoca vitulina), la tintorera (Prionace glauca), Amblyraja radiata, la clavellada (Raja clavata), la llunada fistonada (Sphyrna lewini), l'agullat (Squalus acanthias), l'ànec glacial (Clangula hyemalis), Loligo forbesi, la canana del nord (Illex illecebrosus), la marsopa comuna (Phocoena phocoena) i Eledone cirrhosa.[18]

És parasitat per Goussia clupearum, Eimeria sardinae, Ceratomyxa auerbachi, trematodes del gènere Hemiurus, nematodes (Hysterothylacium aduncum i Anisakis simplex) i Cryptocotyle lingua.[19][20]

L'areng va jugar, i encara el fa, un paper molt important com a aliment bàsic a Europa i a Nord-amèrica. La seua pesca a Suècia es remunta al segle X i als Països Baixos cap a l'any 1167.[21] A l'Edat Mitjana (segle XIV) ja es va començar a posar-los en barrils de fusta en salmorra i la seua importància als Països Baixos fou tal que els habitants d'Amsterdam diuen que la seua ciutat la van construir sobre espines d'areng.[22] Al segle XV, els Països Baixos i França van signar un tractat per dividir-se les zones de pesca d'aquest peix.[23] L'areng fou l'aliment principal de la Quaresma i s'anomenava el blat de la mar.[24]

A la península Ibèrica es ven generalment fumat i envasat en plàstic (no s'ha de confondre amb l'arengada que es ven en els típics barrils cilíndrics de fusta i que són sardines en salmorra), fresc, congelat, en conserva o salat. La seua carn és molt apreciada, tant pel seu gust com pel seu valor nutricional (és molt rica en greixos i té un alt contingut en àcids grassos omega 3, la qual cosa el converteix en un aliment molt cardiosaludable. A més és una font de proteïnes, seleni, fòsfor, iode, vitamina D i algunes vitamines del grup B -niacina i riboflavina-).[17][25] També es pot trobar envasat en flascons transparents, conservats en vinagre molt suau, en filets enrotllats que envolten ceba dolça i cogombres anomenats roll-mops i que són molt populars al nord d'Europa.[26]

Pel que fa a l'Amèrica del Nord, els nadius americans van ésser els primers a emprar un sistema de rescloses per a la captura de l'areng, ja que era difícil la seua pesca utilitzant els mètodes tradicionals que feien servir fins aleshores (ganxos o llances).[12]

Pesca medieval de l'areng a Escània (publicat el 1555)

L'areng (Clupea harengus) és una espècie de peix de la família dels clupeids i de l'ordre dels clupeïformes. L'areng de l'Atlàntic (Clupea harengus) està estretament relacionat amb l'areng del Pacífic (Clupea pallasii), ja que recents estudis genètics indiquen que aquestes dues espècies van començar a divergir fa aproximadament 1,3 milions d'anys.

Sleď obecný (Clupea harengus), neboli herynek, je nejhojnější rybou na naší planetě, navíc je rybou hospodářsky významnou. Sleď obecný obývá vody Atlantského oceánu v obrovských hejnech. Má standardní délku 45 cm. Hmotnost takto vzrostlého jedince se pohybuje kolem 0,5 kilogramu. Sledi se živí planktonními klanonožci, krilem a malými rybkami. Jejich přirozenými predátory jsou ploutvonožci, kytovci, tresky a jiné větší ryby.

Sleď obecný má standardní délku 45 cm při hmotnosti těla 0,5 kg. Maximální zjištěná hmotnost dosáhla 1,050 kg. Maximální zjištěná délka života činila 25 let.

Sleď obecný má protáhlé štíhlé tělo, na průřezu oválné, ale se znatelně vyvinutým břišním kýlem. V porovnání se šproty (Sprattus sprattus) je bříško zakulaceno.

Hřbetní ploutev (tvrdé paprsky): 0–0; hřbetní ploutev (měkké paprsky): 13–21; řitní ploutev (tvrdé paprsky): 0; řitní ploutev (měkké paprsky): 12–23; obratlů: 51–60.

Sleď obecný se liší od jiných sleďů, kterých je téměř 200 druhů v čeledi Clupeidae, svou poměrně malou velikostí; jejich šupiny jsou poměrně velké, tenké bez nápadného kýlu, velice snadno odpadávají; hlava je lesklá, přičemž skřele ani hlava nejsou kryty šupinami; žaberní víčko je bez paprsčitého rýhování. Oko sledě je opatřeno tukovými víčky. Ocasní ploutev hluboce vykrojená. Sledi mají břišní ploutev, která je spíše za krátkou hřbetní ploutví; hřbetní ploutev je přibližně uprostřed jejich těla. Nemají tukovou ploutvičku, což odlišuje sledě od čeledi lososovitých. Na rozdíl od jiných sleďů mají také shluk drobných oválně uspořádaných zoubků na horním patře tlamičky; dolní čelist je delší než horní a také ji přesahuje. Postranní čára není patrná.

Stříbřitá barva s namodralým či nazelenalým hřbetem. Žádné charakteristické skvrny na těle ani na ploutvích.

Sledi dosahují pohlavní dospělosti po 3 až 9 letech. Třou se v hejnech. Zajímavé je, že jednotlivé rodové linie kladou jikry nezávisle na sobě během celého roku, tedy každá v jiný měsíc a na jiném místě. Sledi kladou jikry na mořské dno, skály, kameny, štěrk, písek, ale kladou jikry také na chaluhy. Nakladené jikry neopatrují.

Jikry jsou kulaté, žloutek není zcela průhledný a je nehomogenní. Jikry jsou hladké, ale lepkavé; neobsahují olejové kapénky. Velikost jiker se pohybuje mezi 1,57 a 1,91 mm u populací z Islandu.

Sleďovité ryby jsou nejdůležitější skupinou ryb na naší planetě, Clupea harengus harengus je nejčetnější rybou a je hlavním požíračem obrovského množství zooplanktonu. V prvním roce se sledi živí malými planktonními klanonožci (Copepoda), následně se živí klanonožci (hlavně Calanus finmarchicus a Temora longicornis), ale také různonožci, drobnými korýši z řádu krunýřovek, garnáty, malými rybkami, červy, žebernatkami.

Na druhou stranu je sleď hlavní kořistí ve vyšších trofických úrovních. Příčiny jejich úspěchu zůstávají stále záhadou. Některé úvahy vysvětlují jejich dominanci pozoruhodným životem v obrovských, rychle se pohybujících hejnech.

Ačkoli sleď obecný žije v severských vodách kolem Arktidy, nejedná se o vysloveně arktický druh. Je to nejen pelagický druh sestupující do maximálních hloubek 200 metrů. Přes den setrvává ve větších hloubkách. Migruje na velké vzdálenosti.

Sleď obecný se nachází na obou stranách Atlantského oceánu. Pohybuje se v širokém rozmezí od Mainského zálivu, zálivu svatého Vavřince, zálivu Fundy, Labradorského moře, Davisova průlivu, Beaufortova moře, Dánského průlivu, Norského moře, Severního moře, Baltského moře, La Manche, Keltského moře až po Biskajský záliv.

Severoatlantická hejna sleďů zabírají neuvěřitelné 4 km³, přičemž tato hejna mají až 4 miliardy jedinců.

Sleď obecný je užitkovou a ekonomicky velice významnou rybou. Podle FAO bylo v roce 1999 vyloveno 2 403 543 tun, přičemž se na tomto množství nejvíce podílelo Norsko s 821 435 tunami a Island s 343 769 tunami. Maximální výlov byl v roce 1966, kdy bylo vyloveno 4 095 394 tun. Minimální výlov byl v roce 1979, kdy činil pouhých 887 533 tun. V obchodech je prodáván jako uzenáč, pečenáč, matjesové filety, slaneček, zavináč, herinky aj.

Sledi se zpracovávají čerství, suší se, nakládají se do soli, udí se, konzervují a mrazí. Mohou být smaženi, vařeni, pečeni i upravováni v mikrovlnných troubách.

Sledi obecní byli dlouho důležitou hospodářskou součástí rybolovu Nové Anglie a kanadských přímořských provincií, protože se zdržovali poměrně blízko pobřeží ve velkých hejnech, zejména v chladných vodách polouzavřeného Mainského zálivu a zálivu svatého Vavřince. Dnes je jejich výlov již regulován.

Tabulka udává dlouhodobě průměrný obsah živin, prvků, vitamínů a dalších nutričních parametrů zjištěných v mase sledě.[2]

Složka Jednotka Průměrný obsah Prvek (mg/100 g) Průměrný obsah Složka (mg/100g) Průměrný obsah voda g/100 g 57 – 79 Na 120 vitamin C stopy bílkoviny g/100 g 17,8 K 320 vitamin D 0,007 – 0,031 tuky g/100 g 5 – 20 Ca 60 vitamin E 0,76 cukry g/100 g 0 Mg 32 vitamin B6 0,44 celkový dusík g/100 g 2,85 P 230 vitamin B12 0,013 vláknina g/100 g 0 Fe 1,2 karoten stopy mastné kyseliny g/100 g 11,5 Cu 0,14 thiamin 0,01 cholesterol mg/100 g 50 Zn 0,9 riboflavin 0,26 Se mg/100 g 0,035 I 0,029 niacin 4,1 energie kJ/100 g 791 Mn 0,04 Cl 170Sleď obecný (Clupea harengus), neboli herynek, je nejhojnější rybou na naší planetě, navíc je rybou hospodářsky významnou. Sleď obecný obývá vody Atlantského oceánu v obrovských hejnech. Má standardní délku 45 cm. Hmotnost takto vzrostlého jedince se pohybuje kolem 0,5 kilogramu. Sledi se živí planktonními klanonožci, krilem a malými rybkami. Jejich přirozenými predátory jsou ploutvonožci, kytovci, tresky a jiné větší ryby.

Sild eller atlantisk sild (Latin:Clupea harengus, engelsk: herring) er en fisk i sildefamilien. Det er en overfladefisk, der lever i store stimer, hvor der kan være op til en million individer. Silden findes på begge sider af det nordlige Atlanterhav. Ud for Nordamerika findes silden fra Cape Cod til Labradorkysten, Sydgrønland og Island. Ved Europa findes den fra Biscayen til Barentshavet og Hvidehavet. Der findes sild ved alle danske kyster, og i Østersøen når den helt ind i Bottenhavet.[1]

Silden er en slank fisk, der sjældent bliver over 35 centimeter lang. Skællene er tynde, og den mangler en sidelinje. Silden har underbid og glatte gællelåg. Den ligner brisling, men kendes fra denne ved, at rygfinnerne sidder længere fremme end bugfinnerne.[1]

Den levende sild er blågrøn på ryggen, mens sider og bug er sølvskinnende uden pletter. Den døde sild er mere blålig på ryggen og nedadtil rent sølvhvid. Ligesom de fleste andre fisk er silden mørk på oversiden og lys på undersiden. På den måde er den mindre synlig i vandet fra alle vinkler, fordi lyset i de øverste vandmasser kommer oppefra.

Sildens gydning kan forekomme på alle årstider. Den foregår som massegydning, hvor alle fisk gyder æg og sæd samtidig. Æggene er cirka 1,5 millimeter store og tungere end vand, så de synker til bunds. Efter 10-14 dage klækkes de, og de 7 millimeter store larver søger op til overfladelagene for dér at leve af dyre- og planteplankton. Larven er gennemsigtig og meget langstrakt. Ved en længde på 4 centimeter begynder skællene at dannes, og kroppen får sildefacon. Væksten er hurtigst i Nordatlanten ved Island og Norge, hvor silden bliver kønsmoden, når den er 3-7 år gammel og måler 25-35 centimeter. I Østersøen bliver den tidligere kønsmoden, mens dens vækst til gengæld er mindre.

Sild æder plankton, fx krebsdyr som vandlopper og krill, samt fiskeæg og fiskeyngel. De fleste af disse smådyr lever af planteplankton. Der er derfor særligt mange sild i områder, med meget planteplanton. Eksempelvis i Vadehavet, som er rigt på mange af de smådyr, som silden lever af.

Mange andre dyr lever af sild. Allerede som æg er den yndet føde for fx torsk, kuller og andre bundfisk. Småsildene jages i de øvre vandlag af fx makrel, hvilling, torsk, havørred, tobis og måger. Generelt bliver den forfulgt af alle havets rovfisk samt nogle pattedyr. Flere eksempler er laks, hornfisk, hajer, sæler og marsvin. Desuden er silden et vigtigt bytte for garnfiskere.

Sildefiskeriet i Øresund kendes fra kilder tilbage i 1000-tallet, men menes at have taget fart omkring år 1200, hvor Saxo, nok med en vis overdrivelse, beskriver, hvordan der i fangstsæsonen var så mange sild, at de kunne fanges med de bare hænder.

I senmiddelalderen havde fangsten af sild en helt afgørende betydning for økonomien i Nordeuropa. Særligt fangsten i Øresund var af stor betydning. Den udgjorde intet mindre end den tredjestørste handelsvare på europæisk plan (efter korn og klæde). Sammen med fiskeri af torsk var silden af dobbelt så stor betydning som Danmarks næststørste eksportvare: Stude. [2] Det store sildemarked blev holdt i Falsterbo, som udviklede sig til et nordeuropæisk handelscentrum. Også Københavns vækst som handelsby har i høj grad været betinget af de rige forekomster af sild i Øresund. Hovedindtægterne gik dog til hanseatiske købmænd, som havde monopol på handelen med de – hovedsageligt – dansk-fangede fisk.

Beregninger viser, at der i slutningen af 1300-tallet sandsynligvis har været eksporteret 27.000 tons sild årligt – svarende til 300.000 tønder saltet sild. Med et skønnet lokalt forbrug oveni, anslås den samlede fangst at have ligget omkring 36.000 tons. [2] Til sammenligning var fangsten omkring år 1900, med langt mere moderne fangstmetoder, faldet til omkring 20.000 tons. Den saltede sild var en eftertragtet handelsvare, ikke mindst som følge af de mange kristne fastedage i middelalderen. Op mod halvdelen af årets dage var mod middelalderens slutning fastedage, hvor man ikke måtte spise kød. Her var fisk det oplagte alternativ – for den del af befolkningen, der havde råd. Den fede sild fra Øresund blev anset for at være af særlig god kvalitet og indbragte omkring det dobbelte af, hvad man kunne få for sild fra Limfjorden.

Sildene blev saltet i tønder med salt fra nordtyske stensaltminer og eksporteret ned gennem Europa via de tyske hansestæder. I toldregistre fra 1398-1400 for hanseforbundets vigtigste by, Lübeck, kan man se, at sild var den vigtigste handelsvare af alle. Forskere fra History of Marine Animal Populations (HMAP) har kaldt middelalderens sildefiskeri "the most commercially important fishery in the world". [3]

I midten af 1500-tallet kom det danske fiskeri af sild i krise. Handlen blev gradvist overtaget af nederlandske nordsøfiskere – sandsynligvis affødt af hanseatiske købmænds dårlige forvaltning af deres monopol på sildehandelen ved Østersøens markeder. En anden årsag var, at større nederlandske skibe ikke behøvede at bruge øresundshavnene som mellemstation undervejs til de baltiske havne. [2] Sildefangsten skiftede dermed gradvist til at have Nordsøen som sit hovedområde, og i den danske økonomi overhalede landbruget fiskeriet som den største eksportsektor.

Da sildestimene undlod at komme ind til kysten ved slutningen af 1500-tallet, mente biskoppen i Bergen, Absalon Pedersson Beyer, at det var Guds straf, fordi lensherren havde taget sildetienden fra bygdepræsterne. [4] En anden norsk gejstlig, Peder Claussøn Friis, [5] fandt årsagen til sildens forsvinden i folks utaknemlighed for Guds gaver og usædelige opførsel. Han mente også, at Gud havde advaret folk med en underlig sild, der var blevet fanget i 1587 som et varsel om, at han ville tage denne rige gave fra dem, hvad han da også gjorde. [6]

Sild eller atlantisk sild (Latin:Clupea harengus, engelsk: herring) er en fisk i sildefamilien. Det er en overfladefisk, der lever i store stimer, hvor der kan være op til en million individer. Silden findes på begge sider af det nordlige Atlanterhav. Ud for Nordamerika findes silden fra Cape Cod til Labradorkysten, Sydgrønland og Island. Ved Europa findes den fra Biscayen til Barentshavet og Hvidehavet. Der findes sild ved alle danske kyster, og i Østersøen når den helt ind i Bottenhavet.

Der Atlantische Hering (Clupea harengus) ist einer der häufigsten Fische der Welt, einer der bedeutendsten Speisefische und gehört zur Gattung der Echten Heringe. Er wird seit Menschengedenken besonders an seinen Laichplätzen gefangen. Viele Städte wurden in der Nähe der Laichplätze und Durchzugsgebiete gegründet. Für die Hanse war der Atlantische Hering eines der wichtigsten Handelsgüter. Noch bis in das 20. Jahrhundert hinein war der Atlantische Hering so häufig, dass er als „Arme-Leute-Essen“ galt. Heute sind die Bestände durch starke Befischung und ökologische Probleme in der Ostsee deutlich zurückgegangen.

Der Atlantischer Hering wurde in Deutschland 2021 und 2022[1] zum Fisch des Jahres ernannt.

Die Art verfügt über ein weiträumiges Verbreitungsgebiet im Nordatlantik, das sich vom Golf von Biskaya in die Ostsee und nördlich im Arktischen Ozean bis nach Spitzbergen und Nowaja Semlja erstreckt. In westlicher Richtung dehnt es sich über Island und das südwestliche Grönland bis an die Küsten von South Carolina aus. Der Atlantische Hering lebt in Tiefen bis etwa 360 Meter[2] sowohl pelagisch im Freiwasser als auch in küstennahen Bereichen.

Der schlanke und seitlich abgeflachte Fisch kann eine Körperlänge von etwa 45 Zentimeter und dabei ein Körpergewicht von ungefähr einem Kilogramm erreichen, meist bleibt er jedoch kleiner. Das große, leicht oberständige Maul endet vor dem Hinterrand der mit einem durchsichtigen Fettlid ausgestatteten Augen. Der Rücken ist von stahlblauer, dunkelgrauer oder grünlicher Farbe, während Seiten und Bauch silbrig gefärbt sind. Die Bauchflossen und die Afterflosse sind weißlich transparent. Basis und der obere Rand der Brustflossen sind von dunkler Farbe. Die kurze Rücken- und die tief gegabelte Schwanzflosse erscheinen vollständig dunkel gefärbt. Im Unterschied zur im Habitus recht ähnlichen Sprotte (Sprattus sprattus) befindet sich der Ansatz der Bauchflossen hinter der Vorderkante der Rückenflosse und die Schuppen am Bauch sind abgerundet und nicht gekielt. Ferner unterscheidet sich der Hering durch eine ovale Ansammlung kleiner Zähne am Pflugscharbein (Vomer) von anderen Mitgliedern seiner Familie. Eine Seitenlinie fehlt, es findet sich nur das Kopfkanal-System: ein aus 4 verknöcherten Röhren bestehendes, druckempfindliche Zellen aufweisendes Organ, das eine Orientierung zur Nahrung ermöglicht.[3] In einer mittleren Längsreihe trägt der Hering mehr als 60 seiner relativ großen und nur lose sitzenden Schuppen. Im Körperbau stimmt er mit dem Pazifischen Hering weitestgehend überein.

Der Atlantische Hering lebt in Schwärmen mit teilweise sehr hoher Bestandsdichte. Der Fisch ernährt sich zunächst von Phytoplankton (Algen), später von Zooplankton, wie kleinen Krebstieren, pelagischen Schnecken und Fischlarven, die er auf Sicht jagt und mit Hilfe seiner Kiemenreuse aus dem Wasser filtert. Das Epibranchialorgan ist reduziert. Bei entsprechender Planktondichte geht er dazu über, mit weit geöffneten Maul und Kiemenöffnungen durchs Wasser zu ziehen und so die Nahrung auszuseihen. Dieses „ram feeding“ wird nur kurzzeitig durch Schluckbewegungen unterbrochen. Am Tage hält er sich vorwiegend in tieferen Wasserschichten auf, während er des Nachts seiner Nahrung bei deren Vertikalwanderung an die Oberfläche folgt.

Untersuchungen des Mageninhaltes von ausgewachsenen Heringen haben gezeigt, dass die Tiere im Herbst statt Plankton Fische fressen. Dass Heringe sich auch von Fischen ernähren, war bislang nicht bekannt.[4]

Der Atlantische Hering ist in der Lage, Geräusche zu erzeugen und auch selbst wahrzunehmen. Dank einer Verbindung von der Schwimmblase zum Mittelohr hört er gut – nicht aber Ultraschall, wie ihn Zahnwale zum Orten verwenden.[5] Die Geräusche werden vorwiegend nachts und offenbar durch Ausstoßen von Gas aus einem Schwimmblasen-Porus vor der Afteröffnung erzeugt. Der Zweck dieses Verhaltens ist noch unklar; da sich aber die Geräuschproduktion mit der Größe des Schwarms steigert, kann man es auch als Kommunikation deuten.[6]

Der Zeitpunkt der Fortpflanzungsphase schwankt populationsabhängig stark. Die Paarung des Atlantischen Herings findet küstennah in einer Tiefe zwischen 40 und 70 Metern statt, meist in der Übergangsschicht von Küsten- und dem salzhaltigeren Tiefenwasser. Die weiblichen Tiere geben dabei etwa 20.000 bis 50.000, bei großen Exemplaren ausnahmsweise bis zu 200.000[7] der 1,2 bis 1,5 Millimeter großen Eier ab. Die Befruchtung durch die Männchen erfolgt im offenen Wasser. Brutpflege wird durch die Elterntiere nicht betrieben. Die befruchteten Eier sind klebrig und sinken auf den Grund, wo sie an Steinen, Pflanzen und aneinander haften. Bei einer Wassertemperatur von 9 Grad Celsius schlüpfen die Larven nach zwei Wochen, höhere Temperaturen verkürzen die Reifedauer.[8] Die zwischen 7 und 9 Millimeter großen Larven steigen zur Oberfläche auf, wobei sie sich zum Licht orientieren. Nach etwa einer Woche haben sie ihren Dottersack aufgezehrt und beginnen sich von sehr kleinen Planktonalgen und den Larven von Krebstieren zu ernähren. Mit einer Gesamtlänge von 15 bis 17 Millimeter bilden die Larven ihre Rückenflosse aus. After- und Bauchflossen und die Einkerbung der Schwanzflosse erscheinen bei etwa drei Zentimeter Körperlänge. Ab ungefähr vier Zentimeter Körpergröße werden die Schuppen gebildet und der Nachwuchs beginnt seinen Eltern zu gleichen. Nach drei bis sieben Jahren erlangen die Jungfische die Geschlechtsreife. Der Atlantische Hering kann ein Alter von über 20 Jahren erreichen.

Für eine sehr große Zahl von Arten stellt der Atlantische Hering eine wichtige Nahrungsquelle dar, neben dem Menschen beispielsweise für eine Reihe von Dorschartigen, Thunfischen, Makrelen, Robben und Walen.

Der Heringsfang in der Ostsee ist untrennbar mit dem Aufstieg der Hanse zur regionalen Wirtschaftsmacht verbunden. Der Hering war als eiweißreiches Nahrungsmittel und Fastenspeise im Mittelalter sehr begehrt, zusätzlich hatte er durch Einlegen in Salz oder Salzlake (mit Salz aus Lüneburg) den Vorteil, gut transportiert und gelagert werden zu können.[9] Fastenzeiten waren im Mittelalter sehr ausgedehnt und umfassten bis zu einem Drittel des Jahres.

Die Salzheringproduktion führte unter anderem auch zum Bau der Alten Salzstraße und des Stecknitzkanals zwischen Elbe und Trave, einem der ersten Kanalprojekte der Neuzeit in Mitteleuropa, für den Antransport des Lüneburger Salzes via Lübeck nach Schonen. Die dortigen hansezeitlichen Verarbeitungsplätze, Skanör und Falsterbo, wurden während der Saison im August und September zu Großstädten mit bis zu 20.000 Menschen. Eingelagert in zu einem Fünftel mit Salz gefüllten Fässern aus mecklenburgischem und pommerschem Holz, zertifiziert mit dem eingebrannten Siegel der Stadt Lübeck, wurden die Heringstonnen bis Nürnberg und Regensburg gehandelt.

Ein weiterer wichtiger Handelsweg verlief von den Häfen und Weiterverarbeitungseinrichtungen der Niederlande über den Rhein nach Köln, von wo aus weite Teile des westlichen und südlichen Heiligen Römischen Reiches versorgt wurden. Die niederländischen Produzenten verdrängten zwischen 1380 und 1400 Schonen als wichtigste Herkunftsregion für den in Köln gehandelten Hering. Häufig betrieben Kölner Händler auch Tauschhandel mit Hering aus dem Norden gegen Wein aus dem Süden. Mit dem Fischkaufhausmeister und seinen Helfern bestand eine spezielle Gruppe städtischer Beauftragter, die die Qualität des Herings zu überwachen hatten.[10]

Ab etwa 1500 verminderten sich stetig die Heringsschwärme in der Ostsee, bis sie Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts fast völlig ausblieben. Mit der zunehmenden wirtschaftlichen Bedeutung des Nordseeherings ab dem Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts begann der Aufstieg der niederländischen Generalstaaten und der Niedergang der Hanse.[11]

Massive Überfischung im Nordatlantik, unter anderem auch der Heringsbestände, führte zwischen 1958 und 1975 zu den sogenannten Kabeljaukriegen mit schweren politischen Konflikten zwischen Island und anderen europäischen Staaten. Island weitete darauf schrittweise seine Einflusszone im Nordatlantik bis hin zur 200-Seemeilen-Zone aus und veränderte damit auch das internationale Seerecht und das Völkerrecht. Seither haben internationale Fischerei-Vereinbarungen aber dazu geführt, dass der Hering (im Gegensatz etwa zum Kabeljau) in seinen atlantischen Beständen nicht bedroht ist.

Der Hering zählt als fetter Speisefisch wegen seines Nährwerts mit hohem Eiweißgehalt, einer günstigen Fettsäurenzusammensetzung sowie des Gehalts an Jod und Selen zu den wichtigsten Speisefischen der Welt.[12] Abhängig vom Zeitpunkt des Fangs haben der Ernährungszustand des Herings und die sich jährlich wiederholende Fortpflanzungsphase Einfluss auf die verfügbare Fleischqualität.

Bei der Rohware lassen sich unterscheiden:[13]

Auf den Fangschiffen wird der Hering nach der Vorsortierung meist als Ganzes gleich zur Konservierung gefroren und gelangt in dieser Form in den Großhandel sowie in die Weiterverarbeitung. Die Lebensmittelindustrie bietet den bereits filetierten Hering in unterschiedlichsten Aufbereitungen servierfertig abgepackt, in der Dose oder im Glas an. Eine der bekanntesten Konserven dieses Fisches ist wohl der Hering in Tomatensauce.

Die meisten Arten der Zubereitung und der Konservierung gehen jedoch auf die langen Traditionen und Gewohnheiten in den Ländern des Heringsfangs zurück:

Der Atlantische Hering (Clupea harengus) ist einer der häufigsten Fische der Welt, einer der bedeutendsten Speisefische und gehört zur Gattung der Echten Heringe. Er wird seit Menschengedenken besonders an seinen Laichplätzen gefangen. Viele Städte wurden in der Nähe der Laichplätze und Durchzugsgebiete gegründet. Für die Hanse war der Atlantische Hering eines der wichtigsten Handelsgüter. Noch bis in das 20. Jahrhundert hinein war der Atlantische Hering so häufig, dass er als „Arme-Leute-Essen“ galt. Heute sind die Bestände durch starke Befischung und ökologische Probleme in der Ostsee deutlich zurückgegangen.

Der Atlantischer Hering wurde in Deutschland 2021 und 2022 zum Fisch des Jahres ernannt.

Den Atlanteschen Hierk (Clupea harengus), meeschtens einfach Hierk genannt, ass eng Aart Fësch aus der Famill vun den Hierken (Clupeidae). Hien ass weltwäit ee vun deenen heefegste Fësch an och ee vun de wichtegste vun deenen déi giess ginn.

Am Pazifeschen Ozean lieft eng verwandten Aart, de Pazifeschen Hierk (Clupea pallasii).

Den Atlanteschen Hierk lieft am Nordatlantik, wou säi Verbreedungsgebitt sech am Oste vum Golf vu Biscaya bis an d'Nordmier a bis an d'Nordpolarmier zitt; am Westen ass en iwwer Island eraus bis un d'Küste vu Südgrönland a South Carolina verbreet. Hie lieft an enger Déift vu bis zu 360 m, souwuel am oppene Mier wéi och no un de Küsten.

Den Atlanteschen Hierk (Clupea harengus), meeschtens einfach Hierk genannt, ass eng Aart Fësch aus der Famill vun den Hierken (Clupeidae). Hien ass weltwäit ee vun deenen heefegste Fësch an och ee vun de wichtegste vun deenen déi giess ginn.

Am Pazifeschen Ozean lieft eng verwandten Aart, de Pazifeschen Hierk (Clupea pallasii).

As Heren warrt de Echten Heren (Clupea; Etl.: Heern) betekent. Se höört to de gröttere Grupp vun Heernfisch (Clupeidae).

De Heern (ook Hiern, Hiering un Hering nöömt) is ’n lütten or middelgroten Fisch, de man bloots in de nöördliche Eerdhälft to finnen is. Dat gifft twee Hööftaarden: paziefschen Heern (Clupea Pallassii) un atlantschen Heern (Clupea harengus (harengus)). In Düütschland ward mang de atlantschen noch en Ünnerscheed maakt: Noordseeheern (Clupea harengus harengus) un Oostseeheern (Clupea harengus membras).

De Heern leevt in Stümen, wat de besünnere Naam vun ’n School vun Heern is. He Heern fritt man blots sünnere Orden vun lütte Schalendeerten (Verwandte vun’n Dwarslöper un de Granaat/Krabb), de he mang Plankton findt.

In fröhere Tieden was de Heern de wichtigste Spiesfisch in Noordeuropa. He was billig un was dor wegen ok wat för arme Lüüd’. He was ook een vun de Symbolen för Povertee un harr den Ökelnaam „Arme-Lüüd’-Karpen“. To Tieden, wenn de Heern massenwies to kriegen was, kunnen de Minschen em in Sult inleggen (pökeln), suur (in Etig) inleggen un rökern, dat he nich vergammeln deit. Daar hebbt wi den Bückel, den Matjesheern (un dormit den Matjessalaat) un den Bismarckheern (un dormit den Rollmops un den Heernsalaat) vun arvt. Vun wegen all de Överfischeree is nu nich mehr vääl Heern to kriegen, un arme Lüüd’ könnt em bi de hogen Priesen nu ok nich mehr faken köpen.

As Heren warrt de Echten Heren (Clupea; Etl.: Heern) betekent. Se höört to de gröttere Grupp vun Heernfisch (Clupeidae).

De Heern (ook Hiern, Hiering un Hering nöömt) is ’n lütten or middelgroten Fisch, de man bloots in de nöördliche Eerdhälft to finnen is. Dat gifft twee Hööftaarden: paziefschen Heern (Clupea Pallassii) un atlantschen Heern (Clupea harengus (harengus)). In Düütschland ward mang de atlantschen noch en Ünnerscheed maakt: Noordseeheern (Clupea harengus harengus) un Oostseeheern (Clupea harengus membras).

De Heern leevt in Stümen, wat de besünnere Naam vun ’n School vun Heern is. He Heern fritt man blots sünnere Orden vun lütte Schalendeerten (Verwandte vun’n Dwarslöper un de Granaat/Krabb), de he mang Plankton findt.

In fröhere Tieden was de Heern de wichtigste Spiesfisch in Noordeuropa. He was billig un was dor wegen ok wat för arme Lüüd’. He was ook een vun de Symbolen för Povertee un harr den Ökelnaam „Arme-Lüüd’-Karpen“. To Tieden, wenn de Heern massenwies to kriegen was, kunnen de Minschen em in Sult inleggen (pökeln), suur (in Etig) inleggen un rökern, dat he nich vergammeln deit. Daar hebbt wi den Bückel, den Matjesheern (un dormit den Matjessalaat) un den Bismarckheern (un dormit den Rollmops un den Heernsalaat) vun arvt. Vun wegen all de Överfischeree is nu nich mehr vääl Heern to kriegen, un arme Lüüd’ könnt em bi de hogen Priesen nu ok nich mehr faken köpen.

Sallit (Clupea harengus membras) lea silddi vuollešládja, mii ealli Nuortamearas. Dábálaččat sallit deaddá 30-90 grámma ja lea 14-18 cm guhku, muhtimin juoba 30-35 cm guhku. Sallida hárjeveaksi lea čoavjeveavssi ovdalbealde. Suoma stuorimus sallit deattai 1050 grámma jagis 1950.

Sild (latín Clupea harengus) er vanlig víða um í norðara parti av Atlantshavinum. Undir Føroyum eru 3 sildagreinar. Ein grein gýtir um várið, og av henni er nógv til her. Hin greinin gýtir á heysti og sumri. Av henni er ikki nógv til her. Triðja greinin verður nevnd havsildin. Vísindaliga verður hon skipað undir teir 3 sildastovarnar, vit nevna atlantoskandisku stovnarnir. Havsildin gýtir yviri undir Noregi á vári, hon kemur í føroyskt sjóøki bæði at gýta og leita sær eftir føðslu. Sild er úr vatnskorpuni niður á meira enn 200 m. Norðhavssildin stendur stundum heilt niður á 450 m. Er vanliga djúpari um dagin enn um náttina. Sild er uppsjóvarfiskur og virðismikil fiskur.

Sild er langur og smidligur fiskur, hon er væl hægri enn breið. Hon hevur eina lítla ryggfjøður mitt á bakinum, eina lítla gotfjøður, ið situr aftur móti klingruni, smáar búkfjaðrar, ið sita beint aftan fyri fremra enda á ryggfjøðurini. Hon hevur undirbit.

Sild er í Atlantshavinum úr Biskeiavíkini til Grønlands, norður móti Jan Mayen, Svalbarði og eystur móti Novaja Semlja, í Hvítahavinum og Karahavinum. Eisini er hon í Eystarasalti og Norðsjónum. Vestanfyri úr Grønlandi til Suðurcarolina. Hon er eisini undir Íslandi, Føroyum og Noregi.

Sėlkė (luotīnėškā: Clupea harengus) īr žovės, katra paplėtus Atlanta ondenīnė ėr anuo jūrūs (tam tarpė ė Baltėjės jūruo). Muokslėškā priklaus sėlkēžoviu būriō. Jied smolkius viežēgīvius, zooplanktuona, vuo patės īr jiedis dėdesniem žovėm, rouniam, bongėniam.

Sėlkė īr nuognē puopoliaros jiedis ė tonkiausē īr jiedama sūdėta, marėnouta. Nū sena Lietovuo sėlkės bova vėins glabniausiu pasninka jiediu ė Kūtiu patėikalū. Padoudama ont stala so keptās cėbolēs, boruokielēs, grībās.

Η ρέγγα είναι ένα λιπαρό ψάρι του γένους Clupea το οποίο βρίσκεται στα ρηχά και ζεστά νερά του βόρειου Ειρηνικού και του βόρειου Ατλαντικού ωκεανού και της Βαλτικής.[1] Δύο είδη Clupea αναγνωρίζονται, η ρέγγα του Ατλαντικού (Clupea harengus) και η ρέγγα του Ειρηνικού (Clupea pallasii) και καθεμία χωρίζεται σε υποείδη. Οι ρέγγες είναι κυνηγόψαρα, κινούνται σε μεγάλα κοπάδια, και πλησιάζουν την άνοιξη στις ακτές της Ευρώπης και της Αμερικής, όπου αλιεύονται και συντηρούνται συνήθως παστά ή καπνιστά. Φτάνει σε ηλικία 20 με 25 ετών.

Τα δύο είδη Clupea ανήκουν στην μεγαλύτερη οικογένεια Clupeidae (herrings, shads, σαρδέλες, menhadens), η οποία περιλαμβάνει περί τα 200 είδη με κοινά χαρακτηριστικά. Είναι ασημένια με ένα ραχιαίο πτερύγιο, το οποίο είναι μαλακό, χωρίς στηρικτικό ιστό. Δεν έχουν πλευρική γραμμή και η κάτω γνάθος τους προεξέχει. Το μέγεθός τους ποικίλει ανάλογα με το υποείδος: Η ρέγγα της Βαλτικής (Clupea harengus membras) είναι μικρή, 14 με 18 εκατοστά, η κοινή ρέγγα του Ατλαντικού (C. h. harengus) μπορεί να φτάσει τα 46 εκατοστά (18 ίντσες) και τα 700 γραμμάρια βάρος , και η ρέγγα του Ειρηνικού φτάνει περί τα 38 εκατοστά. Έχει πρασινωπά λέπια, γαλάζια πλάτη και ασημόχρωμη κοιλιά.

Η ρέγγα ζει κοπαδιαστά σε ψυχρά νερά με μέτριο βαθμό αλμυρότητας και πλησιάζει τις ακτές μεταξύ Απριλίου-Ιουνίου. Ζει, κυρίως, στις θάλασσες που περιβάλλουν την Ασία και την Βόρεια Ευρώπη, αλλά και κατά το μήκος των ακτών της Νότιας και της Βόρειας Αμερικής. Σπάνια απαντιέται στην Μεσόγειο θάλασσα, στην περιοχή του Γιβραλτάρ.

Στους εχθρούς της ρέγγας περιλαμβάνονται ο άνθρωπος, τα θαλασσοπούλια, τα δελφίνια, οι θαλάσσιες χελώνες, άλλα κυνηγόψαρα, φώκιες, φάλαινες και άλλα μεγάλα ψάρια.

Οι νεαρές ρέγγες τρέφονται με φυτοπλαγκτόν και καθώς μεγαλώνουν αρχίζουν να τρέφονται με μεγαλύτερους οργανισμούς. Οι ενήλικες ρέγγες τρέφονται με ζωοπλαγκτόν, μικρά ζώα που βρίσκονται στην επιφάνεια των ωκεανών, μικρά ψάρια και προνύμφες ψαριών. Κωπήποδα και άλλα μικρά καρκινοειδή αποτελούν την κύρια μορφή ζωοπλαγκτού με την οποία τρέφεται η ρέγγα. Η ρέγγα τρέφεται κυρίως το βράδυ κολυμπώντας με το στόμα ανοικτό και φιλτράροντας το πλαγκτόν από το νερό.

Οι ενήλικες ρέγγες αλιεύονται για το κρέας τους και τα αυγά τους τα οποία χρησιμοποιούνται συχνά για δολώματα. Η εμπορία ρέγγας αποτελεί σημαντικό τμήμα πολλών εθνικών οικονομιών. Στην Ευρώπη η ρέγγα συχνά αποκαλείται το ασήμι της θάλασσας και η εμπορία της θεωρείται η εμπορικά πιο σημαντική στην ιστορία της αλιείας.[2]

Η ρέγγα αποτελεί βασική πηγή τροφής τουλάχιστον από το 3000 π.Χ. Υπάρχουν πολλοί τρόποι σερβιρίσματος και πολλές τοπικές συνταγές: ωμή, μετά απο ζύμωση, τουρσί, η παλαιωμένη με διάφορους τρόπους.

Οι ρέγγες έχουν μεγάλη περιεκτικότητα Ω-3 λιπαρών.[3] Είναι επίσης πηγές βιταμίνης D.

Οι ρέγγες φέρουν επίσης διοξίνες, όμως πηγές θεωρούν ότι τα πλεονεκτήματα από τα Ω-3 είναι στατιστικά ισχυρότερα από τους ενδεχόμενους κινδύνους λόγων διοξινών.[4] Το επίπεδο διοξινών εξαρτάται από την ηλικία και το μέγεθος του ψαριού. Ρέγγες μικρότερες από 17 εκατοστά μπορούν να τρώγονται ελεύθερα ενώ μεγαλύτερες μπορούν να τρώγονται ανα δεκαπενθήμερο.[5]

Η ρέγγα είναι ένα λιπαρό ψάρι του γένους Clupea το οποίο βρίσκεται στα ρηχά και ζεστά νερά του βόρειου Ειρηνικού και του βόρειου Ατλαντικού ωκεανού και της Βαλτικής. Δύο είδη Clupea αναγνωρίζονται, η ρέγγα του Ατλαντικού (Clupea harengus) και η ρέγγα του Ειρηνικού (Clupea pallasii) και καθεμία χωρίζεται σε υποείδη. Οι ρέγγες είναι κυνηγόψαρα, κινούνται σε μεγάλα κοπάδια, και πλησιάζουν την άνοιξη στις ακτές της Ευρώπης και της Αμερικής, όπου αλιεύονται και συντηρούνται συνήθως παστά ή καπνιστά. Φτάνει σε ηλικία 20 με 25 ετών.

Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) is a herring in the family Clupeidae. It is one of the most abundant fish species in the world. Atlantic herrings can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, congregating in large schools. They can grow up to 45 centimetres (18 in) in length and weigh up to 1.1 kilograms (2.4 lb). They feed on copepods, krill and small fish, while their natural predators are seals, whales, cod and other larger fish.

The Atlantic herring fishery has long been an important part of the economy of New England and the Atlantic provinces of Canada. This is because the fish congregate relatively near to the coast in massive schools, notably in the cold waters of the semi-enclosed Gulf of Maine and Gulf of St. Lawrence. North Atlantic herring schools have been measured up to 4 cubic kilometres (0.96 cu mi) in size, containing an estimated four billion fish.

Atlantic herring have a fusiform body. Gill rakers in their mouths filter incoming water, trapping any zooplankton and phytoplankton.

Atlantic herring are in general fragile. They have large and delicate gill surfaces, and contact with foreign matter can strip away their large scales.

They have retreated from many estuaries worldwide due to excess water pollution although in some estuaries that have been cleaned up, herring have returned. The presence of their larvae indicates cleaner and more–oxygenated waters.

Atlantic herring can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. They range, shoaling and schooling across North Atlantic waters such as the Gulf of Maine, the Gulf of St Lawrence, the Bay of Fundy, the Labrador Sea, the Davis Straits, the Beaufort Sea, the Denmark Strait, the Norwegian Sea, the North Sea, the Skagerrak, the English Channel, the Celtic Sea, the Irish Sea, the Bay of Biscay and Sea of the Hebrides.[1] Although Atlantic herring are found in the northern waters surrounding the Arctic, they are not considered to be an Arctic species.

The small-sized herring in the inner parts of the Baltic Sea, which is also less fatty than the true Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus harengus), is considered a distinct subspecies, "Baltic herring" (Clupea harengus membras), despite the lack of a distinctive genome. The Baltic herring has a specific name in many local languages (Swedish strömming, Finnish silakka, Estonian räim, silk, Livonian siļk, Russian салака, Polish śledź bałtycki, Latvian reņģes, Lithuanian strimelė) and is popularly and in cuisine considered distinct from herring. For example, the Swedish dish surströmming is made from Baltic herring.

Fisheries for Baltic herring have been at unsustainable levels since the Middle Ages. Around this time, the primary Baltic herring catch consisted of an autumn-spawning population. Cooling in the mid-16th century related to the Little Ice Age, combined with this overfishing, led to a dramatic loss of productivity in the population of autumn-spawning herring that rendered it nearly extinct. Due to this, the autumn-spawning herring were largely replaced by a spring-spawning population, which has since comprised most of the Baltic herring fisheries; this population is also at risk of overfishing.[2]

Herrings reach sexual maturity when they are 3 to 5 years old. The life expectancy once mature is 12 to 16 years. Atlantic herring may have different spawning components within a single stock which spawn during different seasons. They spawn in estuaries, coastal waters or in offshore banks. Fertilization is external like with most other fish, the female releases between 20,000 and 40,000 eggs and the males simultaneously release masses of milt so that they mix freely in the sea. Once fertilized the 1 to 1.4 mm diameter eggs sinks to the sea bed where its sticky surface adheres to gravel or weed and will mature in 1–3 weeks, in 14-19 °C water it takes 6–8 days, in 7,5 °C it takes 17 days.[3] It will only mature if its temperature stays below 19 °C. The hatched larvae are 3 to 4 mm long and transparent except for the eyes which have some pigmentation.[4]

Herrings are most seen in the North Atlantic Ocean, from the coast of South Carolina until Greenland, and from the Baltic Sea until Novaya Zemlya. In the North Sea people can distinguish four different main populations. The different herring families are spawning in different periods:

These four populations live outside of the spawn season interchangeably. In their spawn season, each population gathers together on their own spawn grounds.

In the past, there was another, fifth distinct population, the Zuiderzee herring, which spawned in the former Zuiderzee. This population disappeared when the Zuiderzee was drained by the Dutch as part of the larger Zuiderzee Works.

Herring-like fish are the most important fish group on the planet. They are also the most populous fish.[5] They are the dominant converter of zooplankton into fish, consuming copepods, arrow worms chaetognatha, pelagic amphipods hyperiidae, mysids and krill in the pelagic zone. Conversely, they are a central prey item or forage fish for higher trophic levels. The reasons for this success are still enigmatic; one speculation attributes their dominance to the huge, extremely fast cruising schools they inhabit.

Orca, cod, dolphins, porpoises, sharks, rockfish, seabirds, whales, squid, sea lions, seals, tuna, salmon, and fishermen are among the predators of these fishes.

Herring's pelagic–prey includes copepods (e.g. Centropagidae, Calanus spp., Acartia spp., Temora spp.), amphipods like Hyperia spp., larval snails, diatoms by larvae below 20 millimetres (0.79 in), peridinians, molluscan larvae, fish eggs, krill like Meganyctiphanes norvegica, mysids, small fishes, menhaden larvae, pteropods, annelids, tintinnids by larvae below 45 millimetres (1.8 in), Haplosphaera, Pseudocalanus.

Atlantic herring can school in immense numbers. Radakov estimated herring schools in the North Atlantic can occupy up to 4.8 cubic kilometres with fish densities between 0.5 and 1.0 fish/cubic metre, equivalent to several billion fish in one school.[6]

Herring are amongst the most spectacular schoolers ("obligate schoolers" under older terminology). They aggregate in groups that consist of thousands to hundreds of thousands or even millions of individuals. The schools traverse the open oceans.

Schools have a very precise spatial arrangement that allows the school to maintain a relatively constant cruising speed. Schools from an individual stock generally travel in a triangular pattern between their spawning grounds, e.g. Southern Norway, their feeding grounds (Iceland) and their nursery grounds (Northern Norway). Such wide triangular journeys are probably important because feeding herrings cannot distinguish their own offspring. They have excellent hearing, and a school can react very quickly to evade predators. Herring schools keep a certain distance from a moving scuba diver or a cruising predator like a killer whale, forming a vacuole which looks like a doughnut from a spotter plane.[7] The phenomenon of schooling is far from understood, especially the implications on swimming and feeding-energetics. Many hypotheses have been put forward to explain the function of schooling, such as predator confusion, reduced risk of being found, better orientation, and synchronized hunting. However, schooling has disadvantages such as: oxygen- and food-depletion and excretion buildup in the breathing media. The school-array probably gives advantages in energy saving although this is a highly controversial and much debated field.

Schools of herring can on calm days sometimes be detected at the surface from more than a mile away by the little waves they form, or from a few meters at night when they trigger bioluminescence in surrounding plankton ("firing"). All underwater recordings show herring constantly cruising reaching speeds up to 108 centimetres (43 in) per second, and much higher escape speeds.

The Atlantic herring fishery is managed by multiple organizations that work together on the rules and regulations applying to herring. As of 2010 the species was not threatened by overfishing.[9]

They are an important bait fish for recreational fishermen.[10]

Because of their feeding habits, cruising desire, collective behavior and fragility they survive in very few aquaria worldwide despite their abundance in the ocean. Even the best facilities leave them slim and slow compared to healthy wild schools.

Clupea harengus in a barrel

Clupea harengus in a barrel Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) is a herring in the family Clupeidae. It is one of the most abundant fish species in the world. Atlantic herrings can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, congregating in large schools. They can grow up to 45 centimetres (18 in) in length and weigh up to 1.1 kilograms (2.4 lb). They feed on copepods, krill and small fish, while their natural predators are seals, whales, cod and other larger fish.

The Atlantic herring fishery has long been an important part of the economy of New England and the Atlantic provinces of Canada. This is because the fish congregate relatively near to the coast in massive schools, notably in the cold waters of the semi-enclosed Gulf of Maine and Gulf of St. Lawrence. North Atlantic herring schools have been measured up to 4 cubic kilometres (0.96 cu mi) in size, containing an estimated four billion fish.

Haringo (Clupea harengus) estas specio de klupeo, marfiŝo vivanta en la norda Atlantiko kaj grandamase kaptata.

En kuirarto fumaĵita haringo estas fiŝaĵo kio konsistas el haringo kun kapo kaj kelkfoje ankaŭ kun intestoj fumaĵita por konservado kaj gusto.

Haringo (Clupea harengus) estas specio de klupeo, marfiŝo vivanta en la norda Atlantiko kaj grandamase kaptata.

En kuirarto fumaĵita haringo estas fiŝaĵo kio konsistas el haringo kun kapo kaj kelkfoje ankaŭ kun intestoj fumaĵita por konservado kaj gusto.

El arenque, arenque común o arenque del Atlántico (Clupea harengus) es un pez de la familia de los clupeidos, muy común en el norte del océano Atlántico.[1]

Tienen el cuerpo alargado, de color plateado con fondo azulado o azul-verdoso.[2] La talla máxima descrita fue de un ejemplar de 45 cm.[3]

Tanto la aleta dorsal como la aleta anal carecen de espinas; escudos sin quilla prominente, opérculo sin huesos radiantes estriados, con el borde de la abertura de las agallas muy redondeado, no presentan manchas oscuras distintivas ni en el cuerpo ni en las aletas.[1]

Habita ambientes bentopelágicos, oceanódromo,[4] pudiendo encontrarse en aguas templadas a frías en un rango de profundidad entre 0 y unos 360 m.[5]

Forma grandes cardúmenes en aguas costeras importantes como mecanismo anti-depredador,[6] con complejas migraciones tanto en busca de alimento como para el desove, con calendarios que dependen de cada una de las razas que existen. Se alimenta de pequeños copépodos planctónicos en su primer año de vida, para después llevar una dieta fundamentalmente de copépodos; es filtrador-capturador facultativo de zooplancton, es decir, puede cambiar a voluntad de alimentarse filtrando a alimentarse capturando, en función del tamaño de las partículas que encuentra.[6] Pasan el día en aguas profundas, pero suben a la superficie de noche; encuentran su comida usando el sentido de la vista.[1]

La alimentación y el crecimiento son muy lentos durante el invierno, siendo sexualmente activos a una edad entre los 3 y los 9 años.[7] Cada población se reproduce al menos una vez cada año, depositando los huevos sobre el sustrato del fondo.[1]

Es muy frecuente encontrar larvas de cestodos y trematodos como parásitos en sus intestinos.[3]

La talla mínima permitida por la legislación en España para su pesca es de 20 cm, estando esta pesca sometida al sistema de cuotas para evitar su sobreexplotación. Aunque de precio bajo en el mercado tiene una gran importancia comercial por su abundancia y fácil captura, se emplea fundamentalmente para consumo humano, tanto ahumado como fresco; también es buscado en pesca deportiva.[1]

Dentro de la especie Clupea harengus se reconocen tres subespecies consideradas hoy como especies distintas[8]

|coautores= (ayuda) |coautores= (ayuda) |coautores= (ayuda) |coautores= (ayuda) El arenque, arenque común o arenque del Atlántico (Clupea harengus) es un pez de la familia de los clupeidos, muy común en el norte del océano Atlántico.

Atlandi heeringas ehk harilik heeringas (Clupea harengus) on heeringlaste sugukonda heeringa perekonda kuuluv kalaliik.

Atlandi heeringas jaguneb neljaks alamliigiks. Läänemerd asustab räim (Clupea harengus membras). Skandinaavia heeringas ehk kevadkuduheeringas koeb Norra ranniku läheduses, Orkney ja Shetlandi saarte ookeanipoolsetes vetes, Fääri saarestiku ümbruse mandrinõlval ja piki Islandi lõunarannikut. Suvikuduheeringas elab Islandi ja Fääri saarte vetes, Lõuna-Gröönimaa fjordides ning eriti Uus-Inglismaa ja Uus-Šotimaa šelfialal. Põhjamere heeringa kogu elutsükkel möödub Põhjameres. [1]

Atlandi heeringas võib kasvada kuni 45 cm pikkuseks ja kaaluda üle poole kilogrammi. Kõige raskemad isendid kaaluvad märgatavalt üle 1 kg.

Nende peamise toidu moodustavad aerjalalised, krillid, noolussid ja väikesed kalad. Atlandi heeringa vaenlased on hülged, vaalad, tursad ja mitmed teised suuremad kalad.

Atlandi heeringas on maailma üks tähtsamaid töönduskalu. Neil on tohutu ulatuse ja suure produktiivsusega turgutusala. Nende kasv on kiire, eluiga ulatub 15–18 aastani ja tänu sellele koosneb nende kuduasurkond paljudest vanuserühmadest. [1]

Viimastel aastakümnetel on seoses püügi intensiivistumisega palju tähelepanu pööratud heeringa arvukuse uurimisele. Norra teadlased varustasid kümneid tuhandeid kalu terasplaadikestega, mis lasti vedrupüstoli abil heeringa kehaõõnde. Seda märgistamisviisi taluvad heeringad täiesti rahuldavalt. Heeringad lasti merre tagasi. Hiljem kontrolliti püütud heeringatest valmistatud kalajahu elektromagnetitega ja osa märgiseid saadi kätte. Heeringavaru määrati valemi põhjal, mille järgi märgistatud kalade üldhulga ja taaspüütud heeringate suhe võrdub varu ja saagi suhtega. [1]

NSV Liidu ihtüoloogid määrasid hüdroakustilise seadme abil heeringaparvede ruumala talvituskohtades ja nende tiheduse veealuse fotografeerimise teel. [1]

Mõlemad meetodid andsid sarnase tulemuse: skandinaavia heeringate varu ulatus parima täienduse perioodil 12–12,5 miljoni tonnini. [1]

Suvikuduheeringate viljakus on tunduvalt suurem kui skandinaavia heeringatel, aga nende varu on mitu korda väiksem. [1]

Atlandi heeringas ehk harilik heeringas (Clupea harengus) on heeringlaste sugukonda heeringa perekonda kuuluv kalaliik.

Atlandi heeringas jaguneb neljaks alamliigiks. Läänemerd asustab räim (Clupea harengus membras). Skandinaavia heeringas ehk kevadkuduheeringas koeb Norra ranniku läheduses, Orkney ja Shetlandi saarte ookeanipoolsetes vetes, Fääri saarestiku ümbruse mandrinõlval ja piki Islandi lõunarannikut. Suvikuduheeringas elab Islandi ja Fääri saarte vetes, Lõuna-Gröönimaa fjordides ning eriti Uus-Inglismaa ja Uus-Šotimaa šelfialal. Põhjamere heeringa kogu elutsükkel möödub Põhjameres.

Atlandi heeringas võib kasvada kuni 45 cm pikkuseks ja kaaluda üle poole kilogrammi. Kõige raskemad isendid kaaluvad märgatavalt üle 1 kg.

Nende peamise toidu moodustavad aerjalalised, krillid, noolussid ja väikesed kalad. Atlandi heeringa vaenlased on hülged, vaalad, tursad ja mitmed teised suuremad kalad.

Räim ehk läänemere heeringas (Clupea harengus membras) on atlandi heeringa alamliik, kes elab Läänemeres.

Tavaline räim toitub planktonist. Hiidräim on röövkala ja sööb sageli ogalikke.[1]

Räim koeb kõval, kivisel või kruusasel põhjal 2–20 m sügavusel.[1]

22. veebruaril 2007 kuulutati räim Eesti rahvuskalaks.[2]

Räime keha on üsna lame, värvilt hõbedane ning tihti sinakasroheliste toonidega. Selja keskosas asub ainus seljauim. Soomused tulevad kergesti ära. Silmad on mõnevõrra suuremad kui atlandi heeringal.[3]

Tavaliselt on räim teistest heeringatest väiksem, enamasti alla 20 cm pikkune. Suguküpseks saab räim 2–3 aasta vanuselt, kui on 13–14 cm pikk. Esineb ka kiire kasvuga hiidräimi, kelle pikkus on 33–37,5 cm.[3]

Tavaliselt kaaluvad räimed veidi üle 20 g.[4]

Peale suuruse eristab räime teistest atlandi heeringatest väiksem selgroolülide arv. Räimel on neid 54–57.[1]

Eesti rannikuvetes saab eristada kolme räimeasurkonda: Liivi lahe räime, Läänemere kirdeosa avamereräime ja Soome lahe räime. [5] Kuna mõni asurkond koeb varasuvel (mais-juunis) ja mõni sügisel, siis on eristatud ka kevadräime ja sügisräime, kelle kategoriseerimises ja tunnustamises pole ihtüoloogid üksmeelel.

Räim on kohastunud eluks riimvees ja suudab kohati elada isegi magevees, näiteks mõnes Rootsi järves.[1]

Räim on Läänemere peamine töönduskala, andes poole sealsest kalasaagist. Räime püütakse tavaliselt ranna lähedalt seisevvõrkude ja seisevnootadega.[1]

Rohkem kui pool saagist läheb konservide valmistamiseks (sprotid õlis ja räim tomatis). Erilise küpsetusmeetodi abil saadakse poolsuitsuräim. Väiksem osa saagist realiseeritakse jahutatult või külmutatult. Räime marineeritakse, suitsutatakse, praetakse või küpsetatakse hapukoore ja tilliga.

1954–1956 prooviti räime aklimatiseerida Araali merre. Kolm aastat peale marja toomist Araali hakkasid räimed seal juba kudema. Esimestel aastatel kasvas räim Araalis väga hästi, tunduvalt paremini kui Liivi või Visla lahes, kust ta pärineb. Räim sõi vähikesi (Diaptomus ja Dikerogammarus), kuid siiski hakkas räimede arvukus tunduvalt vähenema. Toidupuuduse, vaenlaste ja toidukonkurentide rohkuse tõttu ei tekkinudki Araali meres töönduslikku räimevaru.[1] Väikesearvuline räimepopulatsioon elab Väike-Araalis ka praegu.[6]

Tallinnas Kakumäe asumis on Räime tänav. Tänav ulatub Kakumäe teelt Tiskre ojani ja sealt edasi mööda ojakallast Kakumäe lahe äärde.

Räim ehk läänemere heeringas (Clupea harengus membras) on atlandi heeringa alamliik, kes elab Läänemeres.

Tavaline räim toitub planktonist. Hiidräim on röövkala ja sööb sageli ogalikke.

Räim koeb kõval, kivisel või kruusasel põhjal 2–20 m sügavusel.

22. veebruaril 2007 kuulutati räim Eesti rahvuskalaks.

Sardinzar arrunta edo arinka[1] (Clupea harengus) ur gazian bizi den, arrain espeziea da. Ozeano Atlantikoaren bi aldeetan topatu daiteke.

Sardinzar arrunta edo arinka (Clupea harengus) ur gazian bizi den, arrain espeziea da. Ozeano Atlantikoaren bi aldeetan topatu daiteke.

Silli (Clupea harengus) on Pohjois-Atlantissa elävä parvikala. Itämeren itä- ja pohjoisosissa elävää silliä kutsutaan silakaksi, ja sitä on pidetty erillisenä alalajina (Clupea harengus membras) erotukseksi silliksi yleensä kutsutusta varsinaisesta atlantinsillistä (Clupea harengus harengus), joka on silakkaa suurempi ja rasvaisempi.

Silli elää Atlantissa suurina parvina. Parvessa voi olla jopa neljä miljardia yksilöä.[2] Silli voi kasvaa 45 cm pitkäksi ja painaa suurimmillaan kilon.[3]

Silli on taloudellisesti tärkeä ruokakala. Sen tilastoitu vuotuinen saalis 2010-luvulla on noin kaksi miljoonaa tonnia. Islanti, Norja ja Yhdistynyt kuningaskunta (Englanti) ovat perinteisiä sillinkalastusmaita. Yhdysvalloissa Uuden Englannin rannikolla kalastetaan myös paljon silliä. Silli on arvostettu saaliskala ja sen pyynti tapahtuu pääsääntöisesti troolilla eli laahusnuotalla ja parvet etsitään kaikuluotaimella.

Maissa silliä on yleensä tarjolla vain suolasillinä tai muuten säilöttynä. Aikoinaan sotien jälkeen on ollut kaupoista saatavana myös pakastettua eli "jääsilliä"silakkaakin.

Sillin ensikäsittely tapahtuu jo pyyntialuksilla suolaamalla sillit tynnyreihin. Suolan lisäksi käytetään jonkin verran sokeria. Monenlainen sillien purkitus tehdään vasta maissa, mereltä tynnyreissä tuoduista suolasilleistä. Ennen sillit suolattiin tynnyreihin sellaisenaan, aivan kokonaisina. Nykyään tynnyrisillin saa päättömänä ja pyrstöttömänä, mutta ei suolistettuna. Päätöntä ja pyrstötöntä silliä, samoin kuin ruodotonta sillifilettä, myydään myös yksittäin tyhjiöpakattuna.

Suomessa ja Ruotsissa on tapana marinoida suolasillin filepaloja etikkaa, sokeria, suolaa ja mausteita sisältävissä mausteliemissä (matjessilli, perhesilli, sipulisilli, sinappisilli).

Nykyisin tuoreen atlantinsillin syönti on harvinaista herkuttelua, mutta Suomeen tuotiin silliä 1940-luvulta alkaen 25 vuotta suomalaisella sillilaivastolla, Saukko-laivastolla, jonka kotisatama oli Rymättylän Röölässä. Rymättylän Säilykkeen Saukko-laivasto oli keväisin kolme kuukautta Atlantilla Islannin vesillä sillinpyynnissä, ja laivasto saapuminen heinäkuussa uusien perunoiden aikaan oli aina tapaus, josta kerrottiin laajasti lehdistössä. Laivaston alukset kilpailivat, kuka on ensin perillä. Viimeisen Saukon kapteeni oli Unto Laine (s. n. 1927/1928).[4][5]

Suomalaisten harjoittama sillinpyynti loppui vuonna 1975 sillikantojen romahdettua. Silloin pyyntikiintiöitä alettiin jakaa kalavesien lähivaltioille.[4]

Suomalaiset kuluttavat silliä kesäaikaan puolet koko vuoden kulutuksesta. Uusien perunoiden kanssa se on edelleen suosittu herkku.[6] Rymättylään on kesäkuussa 2010 avattu Silliperinnekeskus Dikseli (dikseli=sillitynnyrin kannen kiristämiseen käytetty työväline).[4]

Silli (Clupea harengus) on Pohjois-Atlantissa elävä parvikala. Itämeren itä- ja pohjoisosissa elävää silliä kutsutaan silakaksi, ja sitä on pidetty erillisenä alalajina (Clupea harengus membras) erotukseksi silliksi yleensä kutsutusta varsinaisesta atlantinsillistä (Clupea harengus harengus), joka on silakkaa suurempi ja rasvaisempi.

Silli elää Atlantissa suurina parvina. Parvessa voi olla jopa neljä miljardia yksilöä. Silli voi kasvaa 45 cm pitkäksi ja painaa suurimmillaan kilon.

Silli on taloudellisesti tärkeä ruokakala. Sen tilastoitu vuotuinen saalis 2010-luvulla on noin kaksi miljoonaa tonnia. Islanti, Norja ja Yhdistynyt kuningaskunta (Englanti) ovat perinteisiä sillinkalastusmaita. Yhdysvalloissa Uuden Englannin rannikolla kalastetaan myös paljon silliä. Silli on arvostettu saaliskala ja sen pyynti tapahtuu pääsääntöisesti troolilla eli laahusnuotalla ja parvet etsitään kaikuluotaimella.

Clupea harengus

Le hareng, aussi appelé au Canada sardine canadienne, et plus exactement, le hareng atlantique (Clupea harengus), est une espèce de poissons appartenant à la famille des Clupeidae. Il se déplace en grands bancs dans les eaux froides, à la fois fortement salées et oxygénées.

Parvenu à maturité à 3 ans, il fraye le long des côtes ou en eaux peu profondes. La femelle libère 20 000 à 100 000 œufs qui se déposent et se développent sur le fond vaseux. Les harengs n'ont pas de comportements migratoires systématiques, mais ils sont présents dans presque toutes les zones froides de l'Atlantique nord et de l'Europe boréale. Ils vivent en profondeur le jour et se rapprochent de la surface la nuit.

Suivant les saisons, et s'adaptant aux eaux qu'ils recherchent, les bancs de harengs peuvent stationner au voisinage des zones marines de faible profondeur, profiter des eaux froides et oxygénées qui coulent vers les fosses par effet cascading et enfin gagner les rivages et les zones à faible fond pour se reproduire.

Au IIIe siècle est attesté le bas latin aringus. Le germanique hâring est à l'origine du mot français hareng comme de l'allemand Hering. La raison en est probablement que les principaux bancs de la mer du Nord sont déjà pêchés et les harengs traités par des locuteurs germaniques. Le commerce du hareng séché ou hareng saur en caque [1] ou en maise a pris une extension considérable au XIIIe siècle. La maise, ou moise, est un tonneau de 1 000 harengs. Mais il constitue dans les contrées rhénanes, du Hunsrück aux Vosges, du Taunus à la Forêt-Noire, une des premières nourritures connues, ne serait-ce que par l'ancienneté du nom alors que ce produit d'exportation antique est au terme d'une longue et lente remontée du fleuve et de ses affluents.

Clupea harengus

Le hareng, aussi appelé au Canada sardine canadienne, et plus exactement, le hareng atlantique (Clupea harengus), est une espèce de poissons appartenant à la famille des Clupeidae. Il se déplace en grands bancs dans les eaux froides, à la fois fortement salées et oxygénées.

Parvenu à maturité à 3 ans, il fraye le long des côtes ou en eaux peu profondes. La femelle libère 20 000 à 100 000 œufs qui se déposent et se développent sur le fond vaseux. Les harengs n'ont pas de comportements migratoires systématiques, mais ils sont présents dans presque toutes les zones froides de l'Atlantique nord et de l'Europe boréale. Ils vivent en profondeur le jour et se rapprochent de la surface la nuit.

Suivant les saisons, et s'adaptant aux eaux qu'ils recherchent, les bancs de harengs peuvent stationner au voisinage des zones marines de faible profondeur, profiter des eaux froides et oxygénées qui coulent vers les fosses par effet cascading et enfin gagner les rivages et les zones à faible fond pour se reproduire.

O arenque,[2] Clupea harengus Linnaeus, 1758, é unha especie de peixe osteíctio mariño da orde dos clupeiformes e familia dos clupeidos, unha das tres que conforman o xénero Clupea.

Esta especie é unha das comercialmente máis importantes no norte do océano Atlántico.

Segundo Eladio Rodríguez,[3] chámanse tamén arenques as sardiñas grandes salgadas ou afumadas.

Ríos Panisse localiza esta denominación en Sada, Ribeira e na península do Morrazo.[4]

É un peixe azul, graxo, de corpo alongado e cor azul azul escura, apardazada ou moura no dorso e prateado no ventre.[5] Non presenta manchas escuras distintivas nin no corpo nin nas aletas. Chega a alcanzar un tamaño de ata 45 cm,[6] aínda que raramente supera os 40, e unha lonxevidade de 20 a 25 anos.[7]

Como todas as especies do xénero Clupea, tanto a aleta dorsal como a anal carecen de espiñas. Ten o opérculo sen estrías, e o bordo da abertura das galadas é moi arredondado. O maxilar inferior é prominente, e é característica unha dobra adiposa no ollo.

Semellante á sardiña, da que se diferencia, ademais de polo seu maior tamaño, por ter os opérculos lisos (na sardiña son estriados), porque a aleta dorsal sitúase na metade posterior do corpo (na sardiña nace por diante do centro do corpo), e pola presenza de máis de 60 escamas grandes ao longo da parte media de cada flanco, en lugar das 30 da sardiña.[7]

Tampouco presenta a quilla prominente típica da sardiña e máis do trancho.[7]

A especie foi descrita en 1758 por Linneo, na décima edición do seu Systema Naturae.[8][9][10]

Nas linguas xermánicas o nome da especie deriva do ingles antigo hering (Angliano), ou hæring (Saxón occidental), do xermánico occidental *heringgaz (fonte tamén do frisón antigo hereng, do neerlandés medio herinc e do alemán Hering e do antigo baixo fráncico *hâring), de orixe descoñecida, é a orixe das palabras Hering, herring, hering e hareng dos modernos alemán, inglés e francés.[11]

No século III aparece rexistrado o termo do baixo latín aringus,[12] do que derivou o aringa italiano, o arenque (galego, portugués e castelán) e o areng (catalán).

Ademais e polo nome que lle impuxo Linneo, a actualmente válido, a especie coñeceuse tamén por numerosos sinónimos:[8]

Os arenques pódense dividir en diferentes poboacións ou "razas", que se distinguen principalmente polo tamaño, a taxa de crecemento, o período de reprodución e as rotas de migración, así como polo número de vértebras.[7]

Ademais das grandes razas migratorias existen varias formas locais non migratorias nos fiordes e pequenas zonas de diversos mares, que son só importantes para a pesca das poboacións locais.[7]

Desde o punto de vista taxonómico, o SIIT distingue tres subespecies:[13][14]

O arenque vive en augas temperadas e pouco profundas, de máis de 200 m de profundidade e ata os 360, no norte do océano Atlántico, desde as costas do norte do Canadá, sur de Groenlandia e norte de Rusia occidental, ata o sur de Francia (golfo de Biscaia), pasando por Islandia, o mar Báltico, illas Británicas e mar do Norte.[7][15]